The phrase “journey to the sea” first occurred to me while reading a story from J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Silmarillion” mythology. Ulmo, the sea god, chose the man Tuor from afar to be his messenger to the elves. He placed in Tuor’s heart a desire to journey westward, towards the coast. When Tuor arrived, he became “enamoured of […] the Great Sea” and “longing for it [was] ever in his heart” (Silmarillion 238). As he stood on the shore, Ulmo appeared to him:

It seemed to [Tuor] that a great wave rose far off and rolled towards the land, but wonder held him. […] The wave came towards him, and upon it lay a mist of shadow. Then suddenly as it drew near it curled, and broke, and rushed forward in long arms of foam; but where it had broken there stood dark against the rising storm a living shape of great height and majesty. (Unfinished Tales 30)

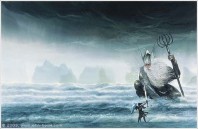

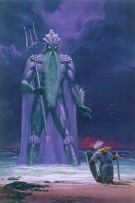

Tuor’s encounter with Ulmo made quite an impression on me, an impression that was deepened after seeing some awe-inspiring works of art illustrating the scene:

While reflecting on the story, I coined the phrase “journey to the sea” to summarize the story and its effect on me. As I continued to contemplate the phrase and study other myths, my affinity for it grew. The two nouns, journey and sea, contain such rich mythic meanings! Let me look briefly at what each of these words means to me.

“Sea”

Sextus Empiricus, a second-century Roman doctor and philosopher, made this observation:

How great is the astonishment the sea causes in a man who beholds it for the first time! (69)

Myth and the sea impact me in similar ways. I have spent most of my life living in landlocked areas, and I still feel this astonishment every time I stand on the shoreline and experience the vastness of the sea, the impressive power of the crashing waves, the delightful sounds of seagulls, and the refreshment of the cool sea breeze. Since childhood, myth has delighted me, instructed me, strengthened me, and taken my breath away. Sometimes these stories fill me with hope and joy; other times, they move me to tears.

In an influential lecture, Tolkien described Beowulf with this analogy:

A man inherited a field in which was an accumulation of old stone. […] Of the [stone] he took some and built a tower. […] From the top of the tower the man [was] able to look out upon the sea. (“Monsters” 105-106)

The tower here refers to the poem itself, the old stone to ancient themes and images the poet incorporated into it. The sea represents the experience myth can produce in its readers, the same experience I described above.

“Journey”

Many myths contain a common pattern of events referred to as the hero’s journey. Scholars have detailed the many different stages and variations in this pattern, but the important stages of this journey for me are these:

- The hero leaves the ordinary world, often prompted by a call to adventure.

- The hero reaches another realm, often with some magical aid, where he completes a set of tasks and achieves some boon.

- The hero returns to the ordinary world, where he uses the boon to benefit others.

This pattern appears in the two stories that had the strongest impact on me in my childhood. In Redwall, the young mouse Matthias recovers the lost sword of ancient lore to save his abbey from the invading rat Cluny the Scourge; in Star Wars, Luke Skywalker learns the ways of a Jedi Knight to rescue his father from the Dark Side and save the galaxy from the tyranny of the evil Empire. These stories resonated with me in ways that I did not fully understand at the time.

Much later, Joseph Campbell’s work introduced me to the power these stories possess for transforming our lives. They can serve as inspiration and models for us to achieve our full potential. Campbell spoke often of a feeling he called “bliss,” a deep satisfaction that comes from “doing what you absolutely must do to be yourself” (xxii). He described life as a hero’s journey to discover what produces this bliss in us, to overcome any trial in our effort to pursue it, and then to benefit others in that pursuit. For me, that pursuit involves myth.

All these thoughts came to my mind when I chose the name Journey to the Sea. This site exists as a way for me to pursue my bliss in myth and to share what I achieve on the journey with others. Through researching and writing articles, I should continue to experience astonishment at myth; I look to other contributors for articles and comments as the magic helpers to aid me in my own journey; and with any luck, the articles I write and my replies to comments will in turn benefit others. I hope that through this site we can all achieve a richer experience of wonder and delight in myths and learn to apply their instruction and wisdom to our everyday lives.

References

- Tolkien, J. R., and Christopher Tolkien. Unfinished Tales. Westminster: Del Rey, 1988.

- Tolkien, J. R.R. The Silmarillion. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2004.

- Sextus Empiricus. Outlines of Pyrrhonism. In Selections from the Major Writings. Trans. Sanford G. Etheridge. Ed. Phillip P. Hallie. Boston: Hackett, 1985.

- Tolkien, J.R.R. “Monsters and Critics.” Beowulf : A Norton Critical Edition. Ed. Daniel Donoghue. Boston: W. W. Norton, 2002.

- Jacques, Brian. Redwall. New York: Penguin, 1987.

- Star Wars. George Lucas. 20th Century Fox, 1977.

- Campbell, Joseph. Pathways to Bliss. “Introduction” (xv-xxii) and “The Self as Hero” (111-134). Chicago: New World Library, 2004.

Image modified and used with permission of John Howe

I haven’t read Campbell’s work so I may be misunderstanding some of what you’re trying to say he says. But I wonder about the idea of reaching our full potential. It sounds good, but what does it really mean? This idea of trying to attain bliss? How does that square with the reality that for most human beings throughout most of history, life has been nasty, brutish, & short? And also dull and monotonous.

I guess I find more sympathy for Tolkien’s view of myth being an escape. Not escapism but myth lifting a person out of the prison of this world for a brief time & showing us something beyond the bare, stark walls of what is called reality. Is Campbell saying something similar? Just curious.

Sorry for taking so long to comment on this but I just got around to reading this article. The Hogshead really takes up too much of my time. :)

@revgeorge – Thanks for stopping by and commenting! Keep up the good work over at thehogshead.org.

This was meant to be a more personal piece than most here at Journey to the Sea. Reading Campbell’s writings on bliss and the hero journey’s in part inspired me to get this site off the ground: the “journey” in the name makes reference to that. So I didn’t attempt to expound Campbell’s position in too much depth. But your question is a fair one. Motivational statements like “be all that you can be” and “strive to reach your full potential” do sound good, but you are right that they are also nebulous, vague, and hard to pin down. But I wouldn’t say that we should just dismiss such talk because we can’t precisely define it.

I think many people long for meaning and value, to feel like they are living for something bigger or more important than just themselves, to know they are not wasting what precious little life they have in insignificant ways. I think everyone has to find their own ways to deal with these longings. Campbell thought that by following your bliss you could reach a state in which you knew “the life that you ought to be living is the one you are living”. This is all of course very individual and very subjective, but I wouldn’t say that makes it any less real.

Campbell would probably agree with you that most people (at least most modern Western people) experience life as something dull and monotonous. But he would probably respond that these people would not be fulfilling their potential and that very few people do. He talked about following your bliss in terms of the hero’s journey pattern: you have to leave your everyday dull and monotonous world to go on some adventure and achieve some boon. Most people do not ever have such an adventure, but the few that do experience life on a whole new plane.

I doubt Tolkien and Campbell would have agreed on much, but I can definitely see some similarities between Tolkien’s escape and Campbell’s journey. I think for Tolkien reading myth brings about a transformation by itself; I think he would say that everyone should read myth. I’m not entirely sure Campbell would say the same thing. It seems that myth was Campbell’s bliss and that studying myth led him to his ideas that we should all go on our own “hero’s journey” — but I’m really not sure if he would recommend that everyone read myth. If pressed, he might say that you should follow your bliss instead of reading myth if the two were at odds.

I like your description of the sea and its impact on you. I too find pleasure and awe looking at the sea; it seems so vast, it’s like looking at the universe itself.

I am also a fan of the Redwall series. Those stories really incorporate the elements that made ancient stories so memorable, like a journey and the battle between good and evil. So good choice including a mention of that!