Where The Wild Things Are, written and illustrated by Maurice Sendak, won the Caldecott Medal as the most distinguished American picture book in 1964. It is now considered a classic of American children’s literature. This book has been a favorite in my family now for going on three generations, with my two-year-old son asking me to read it to him almost every night. While the short text of the story is good, the book is more famous for its beautiful artwork. These images do more than just illustrate the story; in this article, I look at some small details from the artwork and explore how they contribute to what the book has to say about the transforming power of imagination.

The book begins with a boy named Max dressed in a wolf suit misbehaving, terrorizing the dog and talking back to his mother. He is sent to bed without any supper. But a strange thing happens: his room magically transforms into a forest with a nearby ocean. He boards a boat and sails across the ocean for nearly a year before he comes to an island inhabited by terrible monsters known in the book as “wild things.” Max manages to tame them, and they crown him king of all the wild things. After an indefinite amount of time, he grows lonely and wishes to return home. He gives up being king, boards his boat, sails back across the ocean, and returns to his room. He finds there his supper waiting for him.

Many fantasy novels have characters who journey between our world and another world. In some works, like C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia or J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, these other worlds are accepted as true: within the story, that is, they exist as real places. In others, though, like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or The Bridge to Terabithea, the voyages to these other worlds are presented — even within the story — as dreams or as journeys of the imagination. It is not clear how to classify Max’s voyage to the land of the wild things along these lines. The narrator, on the one hand, always describes the events of the story in factual terms:

In Max’s room a forest grew […] and the walls became the world all around. He sailed off through night and day and […] he came to the place where the wild things are. Max stepped into his private boat and waved good-bye and sailed back […] into […] his very own room.

But on the other hand, one subtle element in the artwork convinces me that Max’s adventure is meant to be understood as an imaginary one. An illustration of an early scene contains a picture Max drew before he went on his adventure. Max had not yet been to the place where the wild things are when he made this drawing, yet his drawing looks exactly like one of the wild things he would later meet.

The text of the story does not refer to Max’s drawing at all, but it is an important clue in how to understand the story. I think the similarity between the drawing and the wild thing demonstrates that both originated in his imagination. Even though the narrator takes Max’s journey at face value, I think it is intended to be understood as an imaginary journey.

Throughout this imaginative journey, a change occurs in Max. At the beginning, he is just a naughty little boy. He is eager to escape his room, where he serves his sentence for misbehaving, and imagines himself as the “most wild thing of all” instead of as a well-behaved boy. He sends the wild things to bed without any supper — perhaps directing some negative feelings for his mother towards these innocent creatures of his own imagination. But as he sits alone, he has a change of heart:

Max […] was lonely and wanted to be where someone loved him best of all. […] So he gave up being king of where the wild things are […] and sailed back […] into […] his very own room.

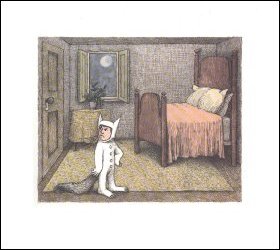

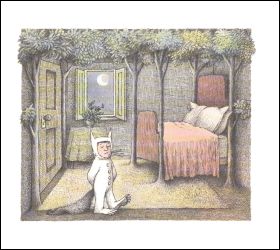

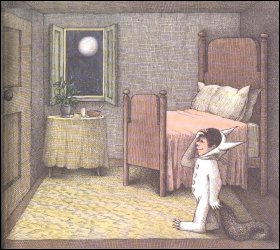

He no longer wishes to be with the wild things: he now wants to be with his mother. Max’s imaginative journey gave him a new perspective on his life, and this new perspective resulted in a different attitude and (presumably) in different behavior after his return. The illustrations capture this effect on Max in a subtle but powerful way. Before Max’s journey, the illustrations of Max’s real world are always contained by a white border on all four sides. As his room transforms into the forest, that border slowly shrinks until the illustrations fill the whole page. (The added black border represents the edge of the page.)

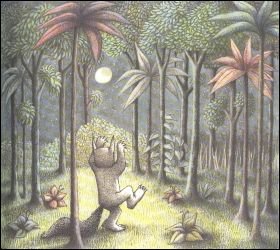

The world of Max’s imagination is larger, more wonderful, and less bounded than the real world. Every page depicting the land of the wild things has illustrations that bleed to the edges of the page; not one of them has a white border surrounding it on all four sides. When Max returns to his room from his imaginative journey, though, the border does not return.

The broadening of the illustration nicely mirrors the broadening of Max’s perspective. In the very first article here, discussing how we define “myth” on this site, I said that the mythic narratives found in ancient mythology and modern fantasy can dramatically change the way we look at our own world. As we read the story of Max’s imaginative journey, we can engage our imaginations to participate to some degree in his journey. We may even be able to have our perspective, our attitudes, and our behavior transformed in a similar way. In both the plot of the story and in some subtle details of the artwork in his Where The Wild Things Are, Maurice Sendak conveyed the role of imagination in this transforming power of mythic narratives.

Reference

- Sendak, Maurice. Where The Wild Things Are. Harper & Row: 1963.

Lovely. I always thought of the voyage taking place in Max’s imagination as well.

What do you make of the phases of the moon? When Max is sent to bed, the moon is a waning crescent, and when he returns, the moon is full. In the pages shown, the moon is actually “going backwards”, going from a later to an earlier phase in its cycle: cf. http://www.samuelwat.com/peabody/images/moonphases.jpg

Peony Moss – I’m glad someone brought up the phases of the moon in the illustrations! I wanted to mention that in my article, but I felt it would take up too much space.

When Max returns, the moon is definitely full. But this doesn’t mean it went backwards one week: it could just have easily gone forward three weeks … or seven weeks … or four hundred and three weeks … or beyond. This is the strongest piece of evidence in the case that Max took a literal journey instead of an imaginative one. He sailed for “almost over a year” to get to where the wild things are, and he sailed for “over a year” to get back. If it was literal, that would have been roughly two years of travel — plus the time he spent with the wild things. The moon very easily could have been full when he returned.

But I think it’s important to note that a waning crescent would only be visible waaaaay past Max’s bedtime. A full moon first rises at sunset; as the moon gets smaller and smaller, it rises later and later. Depending on the exact size of the moon here, it could be well after midnight. (No wonder Max was misbehaving!) I think all the other evidence indicates that the journey was imaginative (most commentators assume this), but then we have to account for the phases of the moon somehow. It should have appeared in the same phase at the end of the journey; if the journey covered any length of time, the moon should no longer have been visible through the window.

Most people do not understand how the moon works, and that fact plays a large part in how I account for the moon in these illustrations. I imagine either that Sendak simply did not understand the moon when he made the illustrations or that he did not feel constrained to depict the moon literally (since most readers wouldn’t notice). Without that knowledge or that constraint, I imagine he decided to use the moon metaphorically. Just like the size of the illustrations grows to fill the page, so too does the light of the moon grow to fill the whole surface. I think the full moon nicely mirrors the broadening of Max’s perspective; he now sees his real world better — as if by more light — than he saw it before his journey.

What medium is used for the illustrations?

It took me a while to track down confirmation, but I found them listed in a few places as this: “Pen and ink, watercolor.” (See here for an example.)

This is such an excellent analysis of the book, and its really helping me with my english assessment to try and analyse the book and how it relates to the journeying aspect (which is what i have to do for year 11 advanced english). Thanks for posting this :DD

In regards to the moon, as mentioned from another person replying, I believe the moon supports the idea that Max is still using his imagination to see the world, even after he returns to his room. More importantly, if we were to compare the first illustration that displays the moon in its incomplete form, with the last illustration of the full moon, It could also be a clue that would support the idea that what Max experienced and where he went was in fact real.

Also, it almost seems as though the plant on the table beside Max’s window has grown fuller, if you actually count the stems. This isn’t a definite clue, but it can support that argument that Max’s journey was real.

Although, an idea that i think hasn’t been brought up already, is that almost every monster has at least one human character trait. One monster has human feet, another human female hair, and another with a striped upper body, almost like a striped jumper. These traits can be linked from Max’s past of course; collective knowledge to be used in Max’s imagination. This is another piece of evidence that further supports the idea that Max was indeed using his imagination to create his journey…. or asleep.

I hadn’t noticed the fuller plant before; thanks for pointing that out! It definitely has more foliage. Just like the fuller moon and the fuller page, I think I would understand the fuller plant as an indication of Max’s internal growth.

(Also interesting to note, it looks like Max’s mom had to move the plant over to make room for Max’s dinner. :~)

I do not understand the popularity of this book as a teaching resource. Personally I do not like the illustrations, the story is lame and perhaps a bit scary for younger students. I do not understand why the moon goes through the phases and that is one of the first things I noticed. If it is so hard for adults to understand why should it be used in a primary classsroom? I just don’t get it. I would rather critically analyse the three little pigs.