Batman has become the eminent expression of the superhero; the character’s recent iterations shape our understanding of the modern mythic hero. Two bards of comics from the 1980s, Frank Miller and Alan Moore, have heavily shaped the perception of the Batman universe of the last twenty-five years. Tim Burton’s films Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992) were clearly informed by their works, and Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins (2005) and The Dark Knight (2008) often paid direct homage to them. Moore and Miller presented Batman as much darker and far more morally ambiguous character than any earlier version.

Before the work of Moore and Miller, Roger B. Rollin examined Batman in conjunction with heroes from other stories of human history like Beowulf and Paradise Lost. At the time of Rollin’s essay in 1970, the dominant version of the Batman story was the campy Adam West television series. Rollin argued that Batman fit the Type II hero identified by Northrup Frye. A hero of this type is human, but he is morally and legally superior to others. This gives him “a semi-divine aura” (Rollin 435) that often seems to place him beyond real human concerns. “Though limited, he is still overwhelmingly powerful and overwhelmingly virtuous” (435). This type of hero presents a unified vision of morality that teaches proper conduct to the reader.

In contrast to Rollin, Robert Jewett and John Shelton Lawrence observed major differences between the heroes of ancient mythology and those of popular American culture. They developed a critical definition of the American pattern, which they argued began in the 1930s and ’40s and continues to the present day:

A community in a harmonious paradise is threatened by evil; normal institutions fail to contend with this threat; a selfless superhero emerges to renounce temptations and carry out the redemptive task. (6)

Although Lawrence and Jewett observed that heroes fitting this pattern were pervasive in American culture, they also found them to be problematic — even contradictory to the point of absurdity:

The monomyth betrays an aim to deny the tragic complexities of human life. […] The American monomyth offers vigilantism without lawlessness […] and moral infallibility without the loss of intellect. […] [The hero] unites a consuming love of impartial justice with a mission of personal vengeance that eliminates due process of law. (47-48)

The blending of “impartial justice” with “personal revenge” played an important role in the shift in the Batman story brought about by Miller and Moore. All versions of the Batman story agree that the motivation for Batman’s creation, his moral code, and his actions is the tragic death of Thomas and Martha Wayne — and Bruce’s deep need to somehow do something about it. Bruce often speaks of the need for justice and the need to save Gotham from criminals at great personal risk, yet he is never quite sure how his own personal feelings of revenge fit this ambition. His antagonists often exploit this conflict, which Miller and Moore explore in their three seminal works, Miller’s Batman: Year One and The Dark Knight Returns, and Moore’s The Killing Joke.

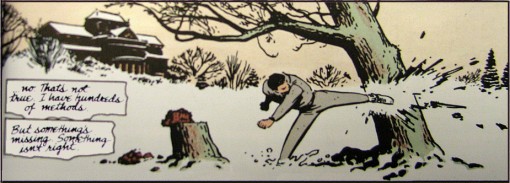

In Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One (1987), a young Bruce Wayne visits the grave of his parents and muses:

I’m not ready […] I have the means, the skill — but not the method . . . no. That’s not true. I have hundreds of methods. But something’s missing. Something isn’t right. I have to wait” (7).

Miller, Frank. Batman: Year One. 1987.

Miller, Frank. Batman: Year One. 1987.

In Miller’s work, Bruce’s extraordinary physical abilities often overwhelm his mental discipline. Almost immediately after leaving the cemetary, Bruce finds himself in trouble when he cannot control his personal motives. He initiates a street fight with a man openly pimping an adolescent girl, and the situation turns into a disaster; Bruce later declares that there is “no excuse — didn’t control myself […] I have everything but patience” (20). The sequence shows a grown Bruce Wayne still driven by adolescent desires that he cannot control — a simple need to act without comprehending the underlying morality of why. The reader is left in a state of confusion as Bruce struggles to clearly define his moral exigence.

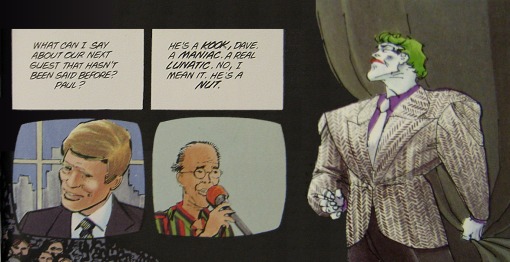

In The Dark Knight Returns (1986), Miller constructs a nearly post-apocalyptic Gotham whose hero has all but abandoned both the city and any righteous motives to the criminals. Fear has run completely amok in Gotham. The public’s lack of effort to stop crime forces Batman’s violent hand. Joker claims to be reformed and appears as a guest on a late-night talk show. When he then massacres the entire studio crowd (121-29), it is up to Batman to use violence in the name of justice. Batman destroys both a gang leader and Joker. But Miller raises a serious concern: should Batman use violence to effect change in society? If his adversaries are using the same tactic, what makes Batman’s actions any better than those he is fighting?

Miller, Frank. The Dark Knight Returns. 1986.

Miller, Frank. The Dark Knight Returns. 1986.

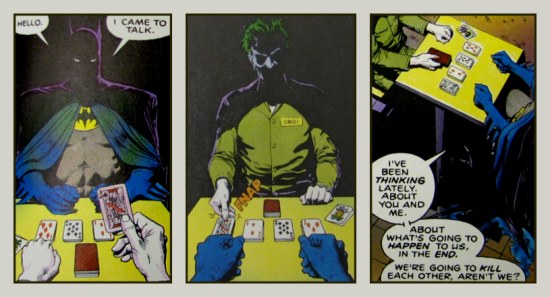

Alan Moore explores fear throughout The Killing Joke (1988) from the opposite perspective, presenting Joker as a kind of negative image of Batman. Nearly every page and panel of the book is saturated in the yellow, purple, and red associated with Joker’s motley suit, giving a strong impression that Joker who terrorizes Gotham City is just as ever-present as Batman who watches over it. Batman doubts his own ability to fight this mirror image. In the book’s opening pages, Batman visits Arkham Asylum and expresses these doubts to Joker:

I’ve been thinking lately, about you and me. About what’s going to happen to us, in the end. We’re going to kill each other, aren’t we? (Moore n.p.)

Moore, Alan. Batman: The Killing Joke. 1988.

Moore, Alan. Batman: The Killing Joke. 1988.

Batman recognizes that his vigilantism and Joker’s terrorism both utilize the same weapon, fear, and Moore presents Batman with an unresolvable dilemma: how can he combat a villain who understands fear as well or even better than he does? The book concludes with Batman and Joker concluding their climactic battle sharing a laugh together over a bad joke, as if in recognition that victory for either of them is impossible.

In the past twenty-five years, the Batman character has grown into a morally complex amalgam of mythic qualities wherein the evolution of his humanity has become more important than any drive toward transcendence. This shift has been primarily the result of the three comic books discussed above, those written by Frank Miller and Alan Moore in the 1980s. According to Lawrence and Jewett’s definition of the American hero, in which the hero must “lift the siege of evil and restore the Edenic state of perfect faith and perfect peace” (46), the Batman of Miller and Moore must be seen as a tragic hero: he cannot overcome his personal flaws and save his community.

References

- Rollin, Roger B. “Beowulf to Batman: The Epic Hero and Pop Culture.” College English 31.5 (Feb. 1970): 431-49.

- Lawrence, John Shelton and Robert Jewett. The Myth of the American Superhero. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 2002.

- Miller, Frank et. al. Batman: Year One. 1986-87. New York: DC Comics, 2005.

- Miller, Frank et. al. The Dark Knight Returns. 1986. New York: DC Comics, 2002.

- Moore, Alan. Batman: The Killing Joke. New York: DC Comics, 1988.

Nice article. I thought your observation that “[n]early every page and panel of the book is saturated in the yellow, purple, and red associated with Joker’s motley suit, giving a strong impression that Joker who terrorizes Gotham City is just as ever-present as Batman who watches over it” was astute, particularly with the panel reproduced below it.

A propos of the subject, I just came across this interesting tidbit. Any comment? :)

Jason, thanks for your comment. The link is interesting, but I don’t know enough about either Robert the Bruce or Wayne to really do much with it. Medieval themes clearly permeate the story. Bruce Wayne would easily be a candidate for knighthood and in a powerful position to enforce justice during the Medieval and early Renaissance periods.

Wow good read. I’m a long time Batman fan but you taught me some things. Now, must go and buy Year One, I seemed to have missed that one d’oh

Бесплатная RPG онлайн игра Техномагия завоевала интерес тысяч пользователей различной возрастной категории оригинальным интерфейсом, геймплеем, игровым движком. Игра в стиле фэнтези совместила в себе элементы стратегии, тактики и логики. Мир Техномагии красочен и ярок, графика основана на флеш-анимации, при этом ее системные требования минимальны.

Laura Branigan – Self Control [url=http://videodisc.tv/search.php?query=%CC%F3%EB%FC%F2%E8%EA%E8-%F3%E6%E0%F1%F2%E8%EA%E8]Мультики-ужастики[/url] лес твинс fick [url=http://videodisc.tv/search.php?query=%C5%EB%E5%ED%E0+%CA%ED%FF%E7%E5%E2%E0]Елена Князева[/url] Sons of Anarchy [url=http://videodisc.tv/search.php?query=%F0%F3%EA%E0%EF%E0%F8%ED%FB%E9+%E1%EE%E9]рукапашный бой[/url]